Field Notes highlights the research and professional activities of students in the Department of History’s doctoral program in Rural, Agricultural, Technological, and Environmental History.

Colton Adkisson is a fourth year PhD student in the RATE program

Tell us about your work. What do you think is new and important about what your research?

Tell us about your work. What do you think is new and important about what your research?

Snag Boats! These unique antebellum steamboats, which were specifically designed in the 1820s for removing debris and obstacles from rivers, sit at the heart of my research and writing interests. For their time they were one of the most advanced pieces of machinery on the frontier and proved to be the crux of a rising river-born commerce, internal improvement spending, environmental exploitation, and a period defining anxiety as Americans surged westward. As new settlers arrived on the Mississippi River, its tributaries became the entry-ways to the West. Snag Boats served the increasingly important task of maintaining the safety and navigability of the Missouri, Arkansas, and Red Rivers to name a few. Understanding their usage, settler reactions to their economic impact, their technical development, and their environmental impact shines new light on the shift from a frontier economy to an established market economy that followed closely behind. The goal of my work, and the research I have been slowly sifting through over the last half a year, is to explain how snag boats helped open up streams of settlement to the antebellum West.

How have you been advancing your work during the pandemic?

Work has been slow but it has not stopped! In lieu of travel over the past 9 months, I’ve turned to online databases to help advance my research. This has turned out to be very fruitful, as I’ve found great material on the Hathi Trust, Archive.org, and Newspapers.com. I’ve spent the lion’s share of my time sifting through antebellum newspapers concerning river improvement. Though the overall pace of my work has been impacted by the pandemic, I’ve slowly been chipping away at my research interests and have built up steam as I go into the early stages of writing my first dissertation chapter.

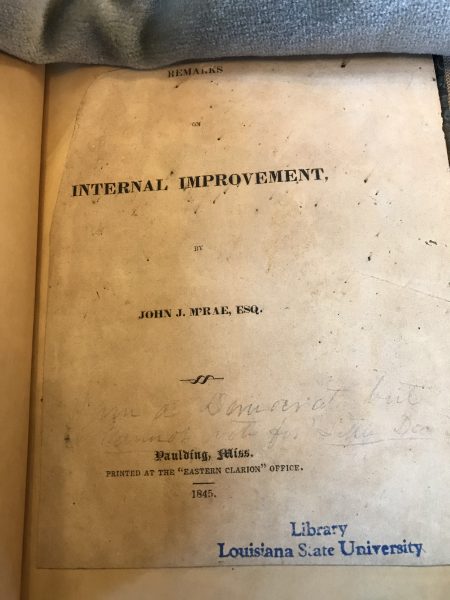

Thankfully, I was able to travel for research outside of Iowa in January. I spent a week down at the Louisiana State University Archives. The Hill Memorial Library and the Special Collections at LSU proved to be rich in documents and sources that I had both expected to find and those that their friendly archivists helped me uncover while I was there. The specific goal of this trip was to look at documents submitted to the Land Claims Office in the early 1800s. To that end it was a very productive trip and I came away with a wealth of historical examples I can work into my writing. Besides the Land Claims Office, the archivists there also uncovered several books pertaining to river improvement that were helpful. The food in Baton Rouge was wonderful and so were the archives!

Looking over the horizon, what’s the big topic you hope to tackle beyond your dissertation?

River improvement and the Civil War. Snag boats did not cease to exist during the war, most were pressed into the service of either the Union or Confederacy. At the start of the war, they either began running supplies or continued keeping the rivers clear. Seeing as my dissertation ends on the eve of the Civil War, it is a natural place to continue digging into the topic. The chaos of the conflict, and the pivotal role the Mississippi River played in the Union strategy as well as the cohesion of the Confederate states, is an exciting backdrop to frame the issue of internal improvement.

Research and teaching are important parts of the work you’ve done here. Are there other professional activities you’re pursuing as well?

The pandemic has definitely allowed for time to expand my portfolio with work not related to my dissertation. I’ve been readying a thesis chapter for publication and chipping away at a book review over the past several months. Though most of my time has been taken up with the aforementioned research, these have come as welcome distractions that have allowed me to focus on other interests and topics.

Along with traditional PhD work, until this past January I also continued on as the ISU History Department’s Career Development Fellow. This position grew out of an American Historical Association grant that was awarded to our department in 2018. The grant’s purpose was to look at department culture and how stu

dents are being prepared for the range of careers and professions that historians now find themselves in. My work as the fellow over the past year has understandably been trying to understand the impact of COVID on student lives and ways in which both our graduate organizations and faculty can help with the obstructions presented by last year’s lockdowns. With the help of the AHA we’ve been able to better understand questions regarding time to degree, student resources, mental health, and other challenges currently facing students in this unprecedented time. Last month I handed this fellowship off to Grace Tomasi, a fellow ISU graduate student, who has eagerly continued on with the grant and the department’s work.

Is there document or piece of evidence that you found particularly interesting or enlightening?

Is there document or piece of evidence that you found particularly interesting or enlightening?

During my trip to LSU, one document in particular proved to be very interesting. One of the key sources that make up the foundation of my research are the reports made by the Chief Engineer of the United States to Congress. These annual reports detail all the river improvement accomplished in the previous year across the breadth of the U.S. At LSU I found a book of these reports and related documents which were compiled by the New Orleans Chamber of Commerce in 1837. This book, which focuses mainly on levee building, breaks down the work completed in the previous years on the Lower Mississippi River is an historical guide to how Antebellum Americans rationalized river improvement as an economic and environmental good. The Chamber of Commerce took notes from Chief Engineer Gratiot’s previous congressional reports and explained what worked and didn’t work to impact the economic growth of the area: where levees had the most impact, the success or failure of cut-offs, and how dredging effected navigability. The book provides insight into the mechanical, economic, and hydrological beliefs that New Orleanians possessed at the time. I would mark my research trip to LSU a success just for getting to look through this book. The fact that it was an aside to my main research goals there, makes it the metaphorical cherry on top!